Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): Concepts and Challenges

This post explores the fast-expanding topic of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), including those that have been approved to date and recent and future innovations that may come to bear on ADCs.

This post explores the fast-expanding topic of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), including those that have been approved to date and recent and future innovations that may come to bear on ADCs.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Concepts and Challenges

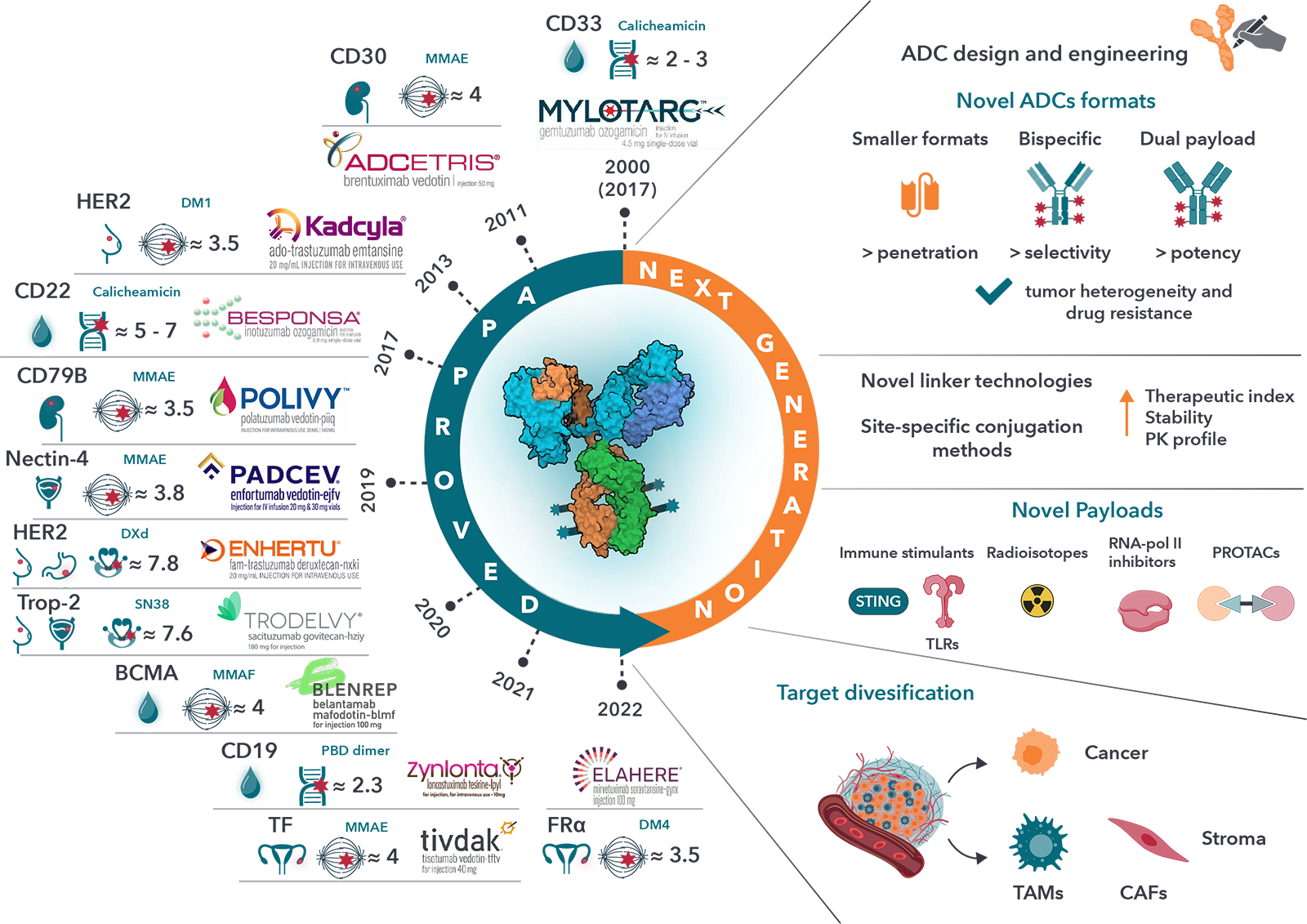

Antibody-Drug Conjugates represent a rapidly expanding class of anticancer agents. While Pfizer’s Mylotarg was the first ADC to gain FDA approval in 2000, serious safety concerns led to its withdrawal from the market in 2010. Despite this preliminary setback, Mylotarg has re-achieved marketing approval and today, there are 15 FDA-approved ADCs on the market.

ADCs represent a unique class of hybrid drugs with three key components: a monoclonal antibody (mAb), a cytotoxin, and a linker molecule that joins the two together. By exploiting the highly specific binding properties of mAbs, potent cytotoxic agents can be selectively targeted and delivered to tumors. This method contrasts with traditional chemotherapies that are non-targeted and non-specific. ADCs’ targeted approach increases the therapeutic index of cell-killing agents for treating cancer and enhances safety by reducing off-target treatment side effects.

The three components of an Antibody-Drug Conjugate and the biologic properties of the cell-surface target antigen are important elements when designing a maximally effective anticancer agent. The classic internalizing ADCs that are currently approved are engineered to specifically deliver highly potent cytotoxic agents to cancer cells that are positive for the targeted antigen. Most ADCs use cleavable linkers that release the cytotoxin once lysosomal internalization occurs due to changes in the surrounding environment, such as the presence of specific proteases and changes in pH. The released drug kills antigen-positive tumor cells, but it may also diffuse out of the target cell and kill antigen-negative tumor cells (the “bystander effect”). In contrast, ADCs with a non-cleavable linker are more likely to kill only target antigen-positive cancer cells; the mAb, and not the linker, undergoes degradation, and since the released drug contains a polar amino acid (from the antibody to which the linker-payload was conjugated), its ability to pass through the cell membrane is severely compromised.

Although Antibody-Drug Conjugates represent an exciting class of anticancer agents, several challenges are hindering their wider development and adoption. These include drug stability, which is a critical issue for optimal storage, patient delivery, efficacy, and safety. Stability poses a significant issue, especially if the drug payload is released prematurely at off-target sites, which can result in toxic off-target side effects. Physical instabilities may also be introduced during manufacturing (e.g., the conjugation process or temperature and light exposure), and these can lead to aggregate formation and diminished drug activity. Even under ideal conditions in which the ADC drops its payload in the tumor, the cytotoxic agents are known to undergo some baseline level of systemic absorption. Without efficient breakdown, the toxin can accumulate in the bloodstream, causing the side effects typically associated with systemic chemotherapy.

Another challenge for ADCs centers on the need for methods to identify the specific patients who are most likely to benefit. Although target antigen expression remains an obvious and important biomarker criterion for patient selection, ADCs have also been effective in patient populations shown to express low levels of the target antigen. Thus, the minimum levels of target antigen expression required for therapeutic efficacy needs to be better understood. The impact of intratumor heterogeneity on antigen expression, and the dynamic changes in expression with treatment and disease progression, are also important considerations.

Finally, resistance remains a major obstacle for all anticancer treatment strategies, including ADCs. Identifying the mechanisms of primary and acquired resistance is not trivial, given their high molecular complexity and that both the mAb and toxic payload could be involved. Downregulation of the target antigen and/or increased expression of multi-drug efflux transporters have been reported in ADC-resistant cancer cells.

Despite these challenges, drug developers are overcoming these common issues as evidenced by the multiple recent FDA approvals and large investments in this category (see next section). A key component to defeating these challenges is to develop a comprehensive preclinical strategy addressing the mechanisms of action, efficacy, toxicity, and biomarker strategy for the novel ADC. Engaging with an experienced preclinical partner early in development can maximize the chances that your ADC will be successful in the clinic.

Commercially Available Antibody-Drug Conjugates

15 ADCs have been approved by the FDA for clinical use. These drugs target a variety of antigens and cellular pathways and deliver different cytotoxic payloads. Lumoxiti®, a recombinant linkerless ADC (often referred to as an “immunotoxin” and generated by the fusion of an antibody fragment with a truncated toxin), has also been approved.

| ADC Name (developing company) |

Antigen | Linker | Payload | Approved disease indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirvetuximab soravtansine (ImmunoGen) |

FR α | Sulfo-SPDB (cleavable) |

DM4 | FR α-positive epithelial ovarian cancer |

| Tisotumab vedotin (Seagen) |

TF | Mc-Val-Cit-PABC (cleavable) |

MMAE | Recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer |

| Disitamab vedotin (RemeGen) |

HER2 | Mc-Val-Cit-PABC (cleavable) |

MMAE | Advanced or metastatic gastric cancer |

| Loncastuximab tesirine (ADC Therapeutics) |

CD19 | Mal-PEG8-Val-Ala- PABC (cleavable) |

SG3199 | Relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma |

| Cetuximab sarotalocan (Rakuten Medical) |

EGFR | Linear alkyl / alkoxy linker (uncleavable) |

IRDye 700DX | Advanced or recurrent head and neck cancer |

| Belantamab mafodotin (GlaxoSmithKline) |

BCMA | Maleimido-caproyl (uncleavable) |

MMAF | Relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma |

| Sacituzumab govitecan (Gilead Sciences) |

TROP2 | CL2A (cleavable) |

SN38 | Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer |

| Enfortumab vedotin (Astellas) |

Nectin-4 | Mc-Val-Cit-PABC (cleavable) |

MMAE | Advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer |

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan (Daiichi Sankyo) |

HER2 | Mc-Gly-Gly-Phe- Gly (cleavable) |

DXd | Unresectable HER2-positive breast cancer |

| Polatuzumab vedotin (Roche) |

CD79b | Mc-Val-Cit-PABC (cleavable) |

MMAE | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| Moxetumomab pasudotox (AstraZeneca) |

CD22 | Mc-Val-Cit-PABC (cleavable) |

PE38 | Relapsed or refractory hairy cell leukemia |

| Inotuzumab ozogamicin (Pfizer) |

CD22 | AcButDMH (cleavable) |

N-acetyl- γ- calicheamicin | B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| Trastuzumab emtansine (Roche) |

HER2 | SMCC (uncleavable) |

DM1 | HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer |

| Brentuximab vedotin (Seagen) |

CD30 | Mc-Val-Cit-PABC (cleavable) |

MMAE | Hodgkin lymphoma; Large-cell lymphoma |

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Pfizer) |

CD33 | AcButDMH (cleavable) |

N-acetyl- γ- calicheamicin | CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia |

[Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Jan 5;52(D1):D1097-D1109.].

ADC research and development is expanding and evolving at an incredible pace, for both hematological and solid tumors, mostly in patients with advanced disease (typically second-line therapy or greater). Some of the recent and major updates were provided at the AACR meeting.

The “ADC renaissance” has led analysts to estimate that the ADC market will reach over $13 billion USD by 2026. This view has also been reflected in the flurry of ADC-related transactions, including Merck’s $1.6 billion licensing deal for Seattle Genetics’ ADC ladiratuzumab vedotin and their buyout of VelosBio (giving Merck access to its anti-ROR ADC), Gilead’s $21 billion acquisition of Immunomedics, which includes their first-in-class anti-TROP-2 ADC, and Boehringer Ingelheim’s acquisition of NBE Therapeutics for $1.2 billion.

Globally, over thousands of Antibody-Drug Conjugates are in development, with “tubulin modulator” agents dominating the pipeline. One study estimated that ~189 ADCs are being actively investigated in clinical trials, including at least 16 in Phase 3 studies [http://adcdb.idrblab.net/, Cancer Commun (Lond). 2024 Jan; 44(1): 3–22.]. In 2023 alone, 55 new ADCs entered clinical trials.

Conclusion

While ADCs are not new from a conceptual perspective, a renewed interest and investment in this important category of drugs is now paying off – with seven of the fifteen approved ADCs gaining FDA approval in the past three years, and decisions on at least three, datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd), patritumab deruxtecan (HER3-DXd) and telisotuzumab vedotin (ABBV-399) expected in 2024 or 2025. Early setbacks led to developing improved bioconjugation methods, advanced antibody engineering technologies, and cytotoxic agents with enhanced stability and safety profiles. Target antigen selection has also improved by leveraging our growing understanding of cell and tumor biology. Together, these innovations have led to an ADC renaissance that has opened potential new avenues for treating cancer patients.

Cite this Article

Hua, A., (2024) Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): Concepts and Challenges - Crown Bioscience. https://blog.crownbio.com/antibody-drug-conjugates-concepts-and-challenges