Precision medicine and immunotherapy are currently two of the hottest areas of cancer research. How can immuno-oncology draw from precision medicine to create more personalized cancer therapies?

Precision medicine and immunotherapy are currently two of the hottest areas of cancer research. How can immuno-oncology draw from precision medicine to create more personalized cancer therapies?

What is Precision Medicine?

Precision medicine refers to the tailoring of medical treatments to the individual characteristics of each patient. This therapeutic customization identifies which approaches will be the most effective for patients based on genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors.

Why Personalized Immunotherapy?

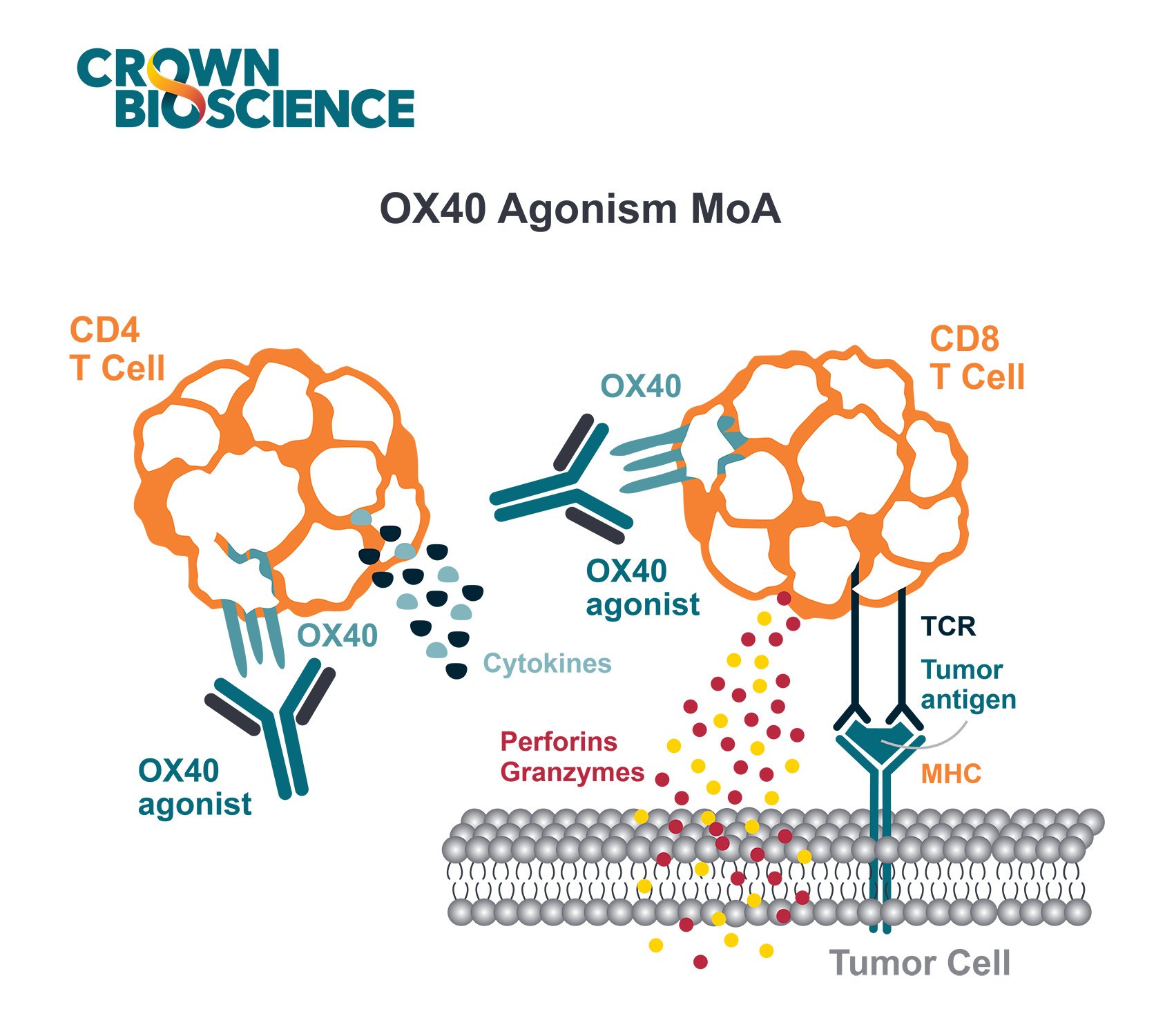

Immunotherapy aims to stimulate (or restore) the patient’s own immune system to combat cancer. Immune checkpoint blockade through anti-PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 inhibitors demonstrates that the immune system is a critical player in fighting cancer, and that immunotherapies are a key new treatment class. They are already being used to successfully treat late stage cancers such as leukemia and metastatic melanoma, and more recently to treat mid-stage lung cancer.

However, only a fraction of patients have a strong response to these agents and patients that receive immunotherapy can experience dramatic side effects. These include severe autoimmune reactions, cancer recurrence, and in some cases, death.

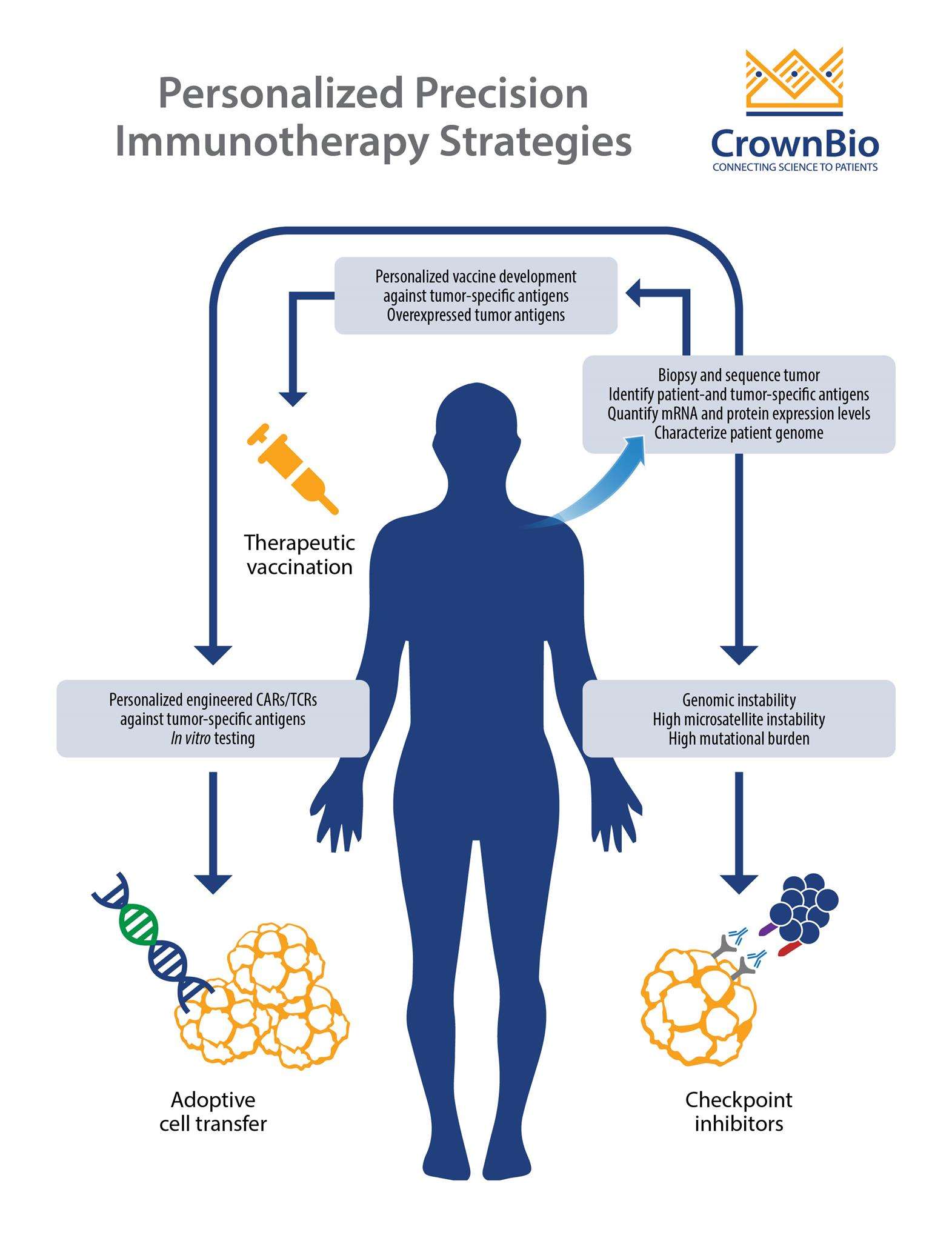

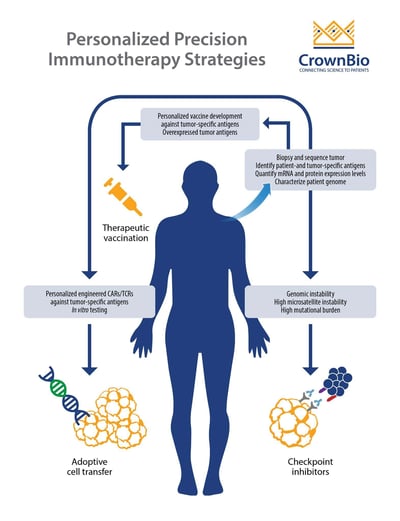

This means that immunotherapy and precision medicine need to combine – to establish which treatments and immuno-oncology strategies will be most effective for different patients and create more personalized cancer immunotherapy.

CAR-T Cell Therapies

One type of personalized immunotherapy which has already been approved for patient use is chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy, a novel immuno-oncology treatment modality.

CAR-T cells are autologous, or allogeneic, T cells which specifically target antigens or markers expressed on tumor cells. The first CAR-T therapy to be FDA approved was Kymriah™ (tisagenlecleucel) in August 2017, which targets the CD19 antigen (the most commonly targeted antigen in CAR-T cell therapy research). Kymriah was approved for the treatment of patients up to 25 years old with relapsed and/or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Approval was based on a remarkable overall remission rate of 82.5%.

This closely followed by an approval for Yescarta™ (axicabtagene ciloleucel), which is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed and/or refractory large B-cell lymphoma, again targeting the CD19 antigen. This approval was based on an objective response rate of 72%.

In May this year, the FDA approved Kymriah for its second indication, the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory large B cell lymphoma after two or more lines of systemic therapy. This includes diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), high grade B cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma. The approval is based on the phase 2 JULIET study, in which the overall response rate to Kymriah was 50% in adult patients.

Is CAR-T Cell Therapy Safe?

As with any new treatment approach, efficacy needs to be effectively monitored, as well as safety. Potentially life-threatening toxicities have been linked to CAR-T cell therapy.

To improve the safety of CAR-T treatment, researchers are now engineering “suicide switches” into the cells. These switches are genetically encoded cell surface receptors that trigger the cell to die when a small molecule drug binds them. If doctors see a patient experiencing side effects, they can prescribe the small molecule drug and induce cell death within thirty minutes.

Other safety strategies include improving the specificity of CAR T-cells for tumor cells through adding a second CAR. This means that the engineered cell has to recognize two antigens to become activated.

Neoantigens

Another way to personalize cancer immunotherapy is to target neoantigens. Neoantigens are proteins which are unique to a cancer, arising from nonsynonymous somatic variations randomly acquired during cell division. This generates highly tumor-specific antigens (expressed exclusively in and on tumor cells), which can be selectively targeted to kill the cancer cell while leaving healthy cells unharmed.

For example, cancers such as lung and melanoma induced by smoking and UV exhibit high mutational loads of neoantigens. Tumors with this burden can potentially harbor immunogenic antigens that can be picked up by the immune system and trigger an antitumor response.

Neoantigens are unique not only to the cancer but also to the individual patient, therefore, they are antigens that the immune system has never encountered. As a result, the body’s defenses should have zero tolerance for a cell bearing a neoantigen. Treatment with a checkpoint inhibitor can unleash neoantigen-specific T cells to fight tumors, increasing both the quality of the antitumor immune response and its magnitude.

Neoantigens provide evidence that the genomic landscape does in fact shape response to immunotherapeutics.

Focusing Neoantigen Antitumor T Cell Response

Checkpoint inhibitors can also elicit T cell responses to nonmutated proteins, thereby diluting the neoantigen-specific response and reducing potential efficacy.

Multiple strategies are being developed to focus neoantigen antitumor T cell response, including:

- Enhancing neoantigen-specific T cell responses by combining checkpoint blockade with therapies that increase the number of potential neoantigens. Treatments like radiotherapy or chemotherapy inducing immunogenic cell death release potential neoantigens. Vaccinating patients with cells derived from their tumors might also increase the number of neoantigens T cells can respond to.

- More personalized strategies consist to develop neoantigen vaccines by identification of mutated proteins in patient’s cancer cells using genomic sequencing. The portions of proteins that could be the most effective neoantigen are then identified to create peptides that go into the vaccine.

Conclusions

For immuno-oncology to fulfill its potential, immunotherapy needs to be personalized by the identification of patient specific immunosuppressive mechanisms and through targeting specific neoantigens.