Learn more about targeting human tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) or tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) in immunotherapy development, including therapeutic approaches and preclinical models for assessing TSA/TAA targeting agents.

Learn more about targeting human tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) or tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) in immunotherapy development, including therapeutic approaches and preclinical models for assessing TSA/TAA targeting agents.

What are Tumor-Associated Antigens and Tumor-Specific Antigens?

There are two major classes of tumor antigen which are targeted by T cell immunotherapies – private antigens and public shared antigens. Public shared antigens are common to multiple patients and are split into two categories:

- Tumor-specific antigens (TSA), found on cancer cells only, not on healthy cells.

- Tumor-associated antigens (TAA), which have elevated levels on tumor cells, but are also expressed at lower levels on healthy cells.

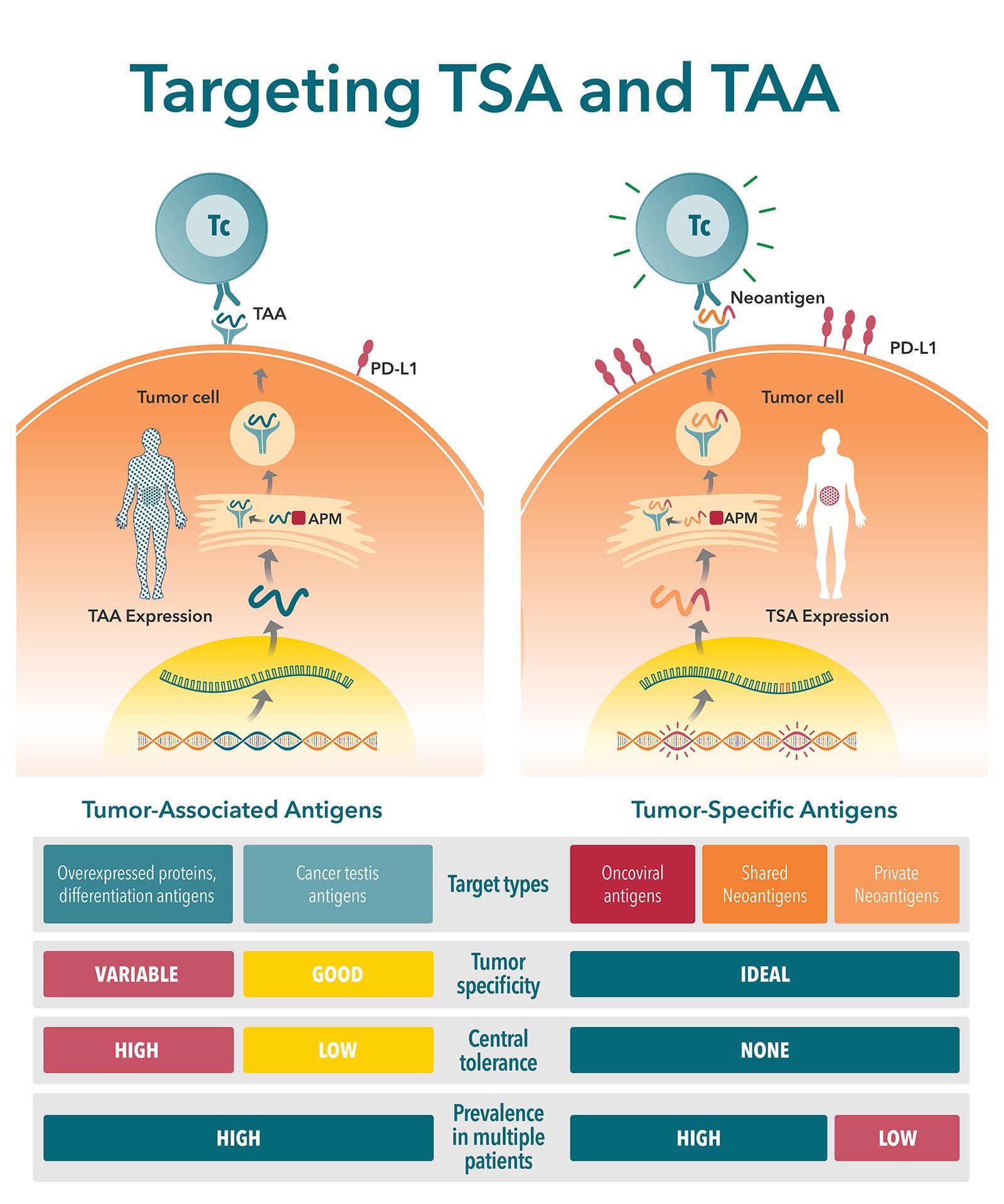

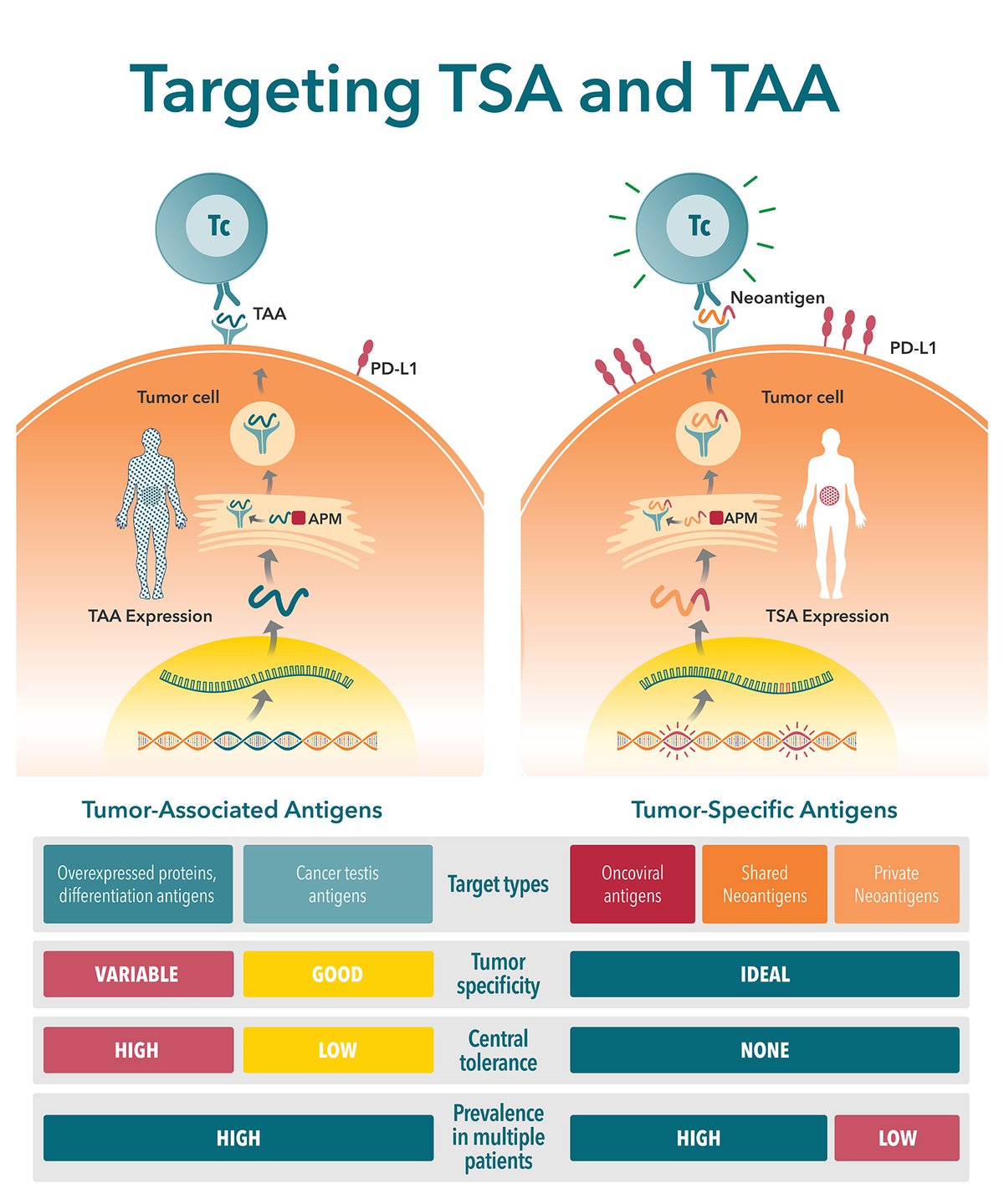

Key Differences Between TSAs and TAAs

There are a number of key differences between TSAs and TAAs. These differences need to be carefully considered when selecting a target antigen. This is a critical step in new agent development, with poorly selected antigens (e.g. with poor expression level or immunogenicity) considered a primary reason for preclinical study failure.

| Tumor-Specific Antigens | Tumor-Associated Antigens |

|---|---|

| Expressed by tumor cells | Self-antigens expressed by tumor cells |

| Not present in normal host cells | Present in a subset of normal host cells |

| Arise mostly from oncogenic driver mutations that generate novel peptide sequences (i.e. neoantigens) | Arise mostly from genetic amplification or post-translational modifications |

| Can also be generated by oncoviruses | Tendency for expression that is higher and preferential for tumor cells |

| Example: Alphafetoprotein (AFP) expression in germ cell tumors and hepatocellular carcinoma | Example: Melanoma-associated antigen (MAGE) expressed in the testis along with malignant melanoma |

Therapeutic Approaches to Targeting TSA/TAA

Many tumor-associated antigens and tumor-specific antigens have been identified and targeting them is considered an important approach in cancer immunotherapy. There are several marketed cancer immunotherapy drugs that rely on this mechanism which are clinically very effective:

- Rituximab is used to treat non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma by targeting the CD20 antigen present on B cells.

- Trastuzumab is used to treat HER2 positive breast cancers by targeting HER2.

These are just two well-known examples among many others.

Developing agents that target TAAs/TSAs remains an intensely active area of research. Countless targeted agents are currently being tested in the preclinical and clinical setting against many different tumor types.

Antibodies against TAAs/TSAs are being used to not only directly kill tumor cells primarily by ADCC effects (e.g. rituximab and trastuzumab) but can also serve as diagnostic markers or to innovatively enhance tumor cell targeting of traditional cancer therapies.

Indeed, conventional cancer treatments such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, antibody immunotherapy, or viral or non-viral nanoparticles tend to not be very specific which leads to safety issues a lack of efficacy. Combining them with antibodies against TAAs/TSAs can increase their ability to specifically target tumor cells.

Bispecific antibodies have shown great promise for improving clinical efficacy and safety, and there are several marketed drugs that use this approach and many others in clinical development. There are three common types of immunotherapeutic bispecific antibodies:

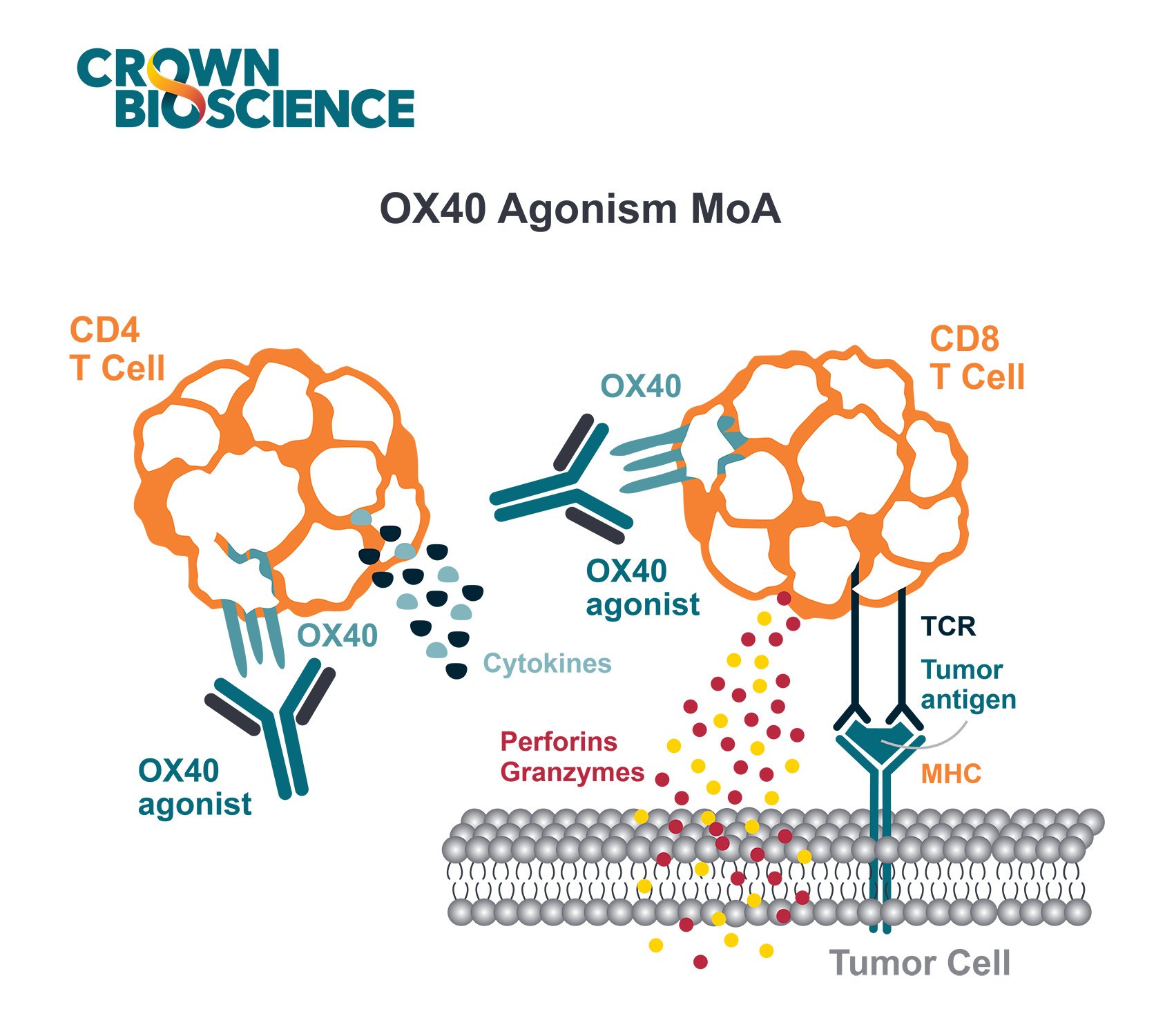

- Cytotoxic Effector Cell Redirectors: These redirect T cell cytotoxicity to tumor cells by using bispecific compounds to engage a TAA/TSA and the T cell receptor/CD3 complex.

- Tumor-targeted Immunomodulators: These are designed to bind to a TAA/TSA and an immunomodulating receptor (e.g. CD40). These compounds are typically intended to be inactive until they bind the tumor antigen, so that the immune stimulation is hyper-localized to the tumor environment, effectively reducing the risk of immune-related side effects.

- Dual immunomodulators: These bind two different immunomodulating targets resulting in blockade of inhibitory targets, depletion of suppressive cells or activation of effector cells (e.g. PD-1xLAG-3, PD-1xTIM-3, PD-1xCTLA-4, CTLA4xOX40).

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy uses T cells that are genetically engineered to produce receptors on their surface (known as “chimeric antigen receptors” [CARs]), which allow T cells to target a specific antigen on tumor cells. The first phenomenal success for CAR-T cell therapy was with CD19, a B cell marker that is highly expressed on malignant B cells. Hundreds of CAR-T clinical studies are currently underway, testing against a variety of TAAs/TSAs.

Cancer vaccines enhance the T cell-mediated antitumor response. A recent resurgence of research in this area is focused on refining therapeutic cancer vaccine technologies, selecting more immunogenic TAAs/TSAs, and using multiple neoantigens to broaden and enhance tumor cell killing. Cancer vaccines are also being tested in combination with checkpoint inhibitors to overcome tumor-induced immunosuppression.

Preclinical Models for Assessing TSA/TAA Targeting Agents

The increased demand for preclinical models for cancer immunotherapy studies has led to a rising need for immunocompetent murine models expressing human TAA/TSA.

Several technologies exist to generate transgenic mice and cell lines that express human TAAs, TSAs, human leukocyte antigen (HLA), or oncogenic or immune checkpoint targets. Selecting the appropriate model is not always straightforward and depends on the experimental immunotherapy strategy, including which tumor targets will be engaged and the specific immune system components that will be activated.

Syngeneic Tumor Models Expressing a Human TAA/TSA

Syngeneic mouse tumor models commonly used to study immunotherapies don’t typically express appropriate TAA/TSAs. This significant challenge is overcome by generating syngeneic mouse tumor models that ectopically express the human TAA/TSA. A relevant mouse cancer cell line is selected, and the cells are modified (e.g. transfected) for this expression. The human antigens then become the target in preclinical testing.

This approach has been widely used and published over many years for the preclinical study of novel TSA/TAA targeting agents across a wide array of targets, including HER2, PSA, TRP-2, EpCAM, GPC3, mesothelin (MSLN), and EGFR.

Transgenic Mice Expressing a Human TAA/TSA

Transgenic mice are often generated to have a murine TAA/TSA knockout and human TAA/TSA knock-in. They can subsequently be bred to achieve antigen expression patterns and levels that are similar to those found in humans, which may increase the clinical translatability of these models.

In addition, using a transgenic model for targeting against a human tumor self-antigen (i.e. TAA) means that the TAA will not be exclusively expressed in the tumor cells (i.e. it will also be expressed in normal host tissue), which models the human situation very well. Therefore, transgenic models are especially valuable to evaluate potential side effects of TAA-specific immunotherapies, such as CAR-T cell therapy.

Transgenic mouse models have also been used extensively for the preclinical study of novel TSA/TAA targeting agents across a wide array of targets, including HER2, CEA, PSA, and MUC1.

Conclusion

Immunocompetent preclinical mouse models that express human tumor-associated antigens and tumor-specific antigens are invaluable for the research and development of new immunotherapies. A better understanding of the available types of models for assessing TAA/TSA-targeting agents increases the chances that the optimal model for your experimental immunotherapy studies will be selected, therefore providing the best opportunity for success.